At a time of national aspiration amid increasing global uncertainty, the Malthouse adaptation of Voltaire’s Candide spoke back to the buzzword of the times. As Rob Reid writes, the internationally acclaimed production became emblematic of Kantor’s directorial style and the company’s new approach to theatre-making.

During his time as Artistic Director of Malthouse Theatre, Michael Kantor made a broad range of sweeping changes to the company, radically altering the programmed content and aesthetic, and initiating major interstate and international collaborations. This approach was at times controversial and rocky, as Kantor himself often argued that the value of a company like The Malthouse was its ability to take risks, but it also resulted in some unquestionably outstanding successes. The years between 2007 and 2009 saw some of his most celebrated works developed, presented, touring and lauded with critical praise, box office success and multiple awards.

One of the most recognized of these was Optimism, an adaptation of Voltaire’s classic novella, Candide, directed by Kantor and written by his longtime collaborator Tom Wright in 2009. The first decade of the new millennium in Australia was one of generational change, particularly in the performing Arts. By the end of the decade the established long term Artistic Directors of many of the flagship theatre companies had largely stepped aside to make way for a new cohort of younger artists, many of whom had risen out of the 1990s independent and alternative theatre scenes, and the emerging artists of the 2000s had established national and international reputations and careers. At the same time however, there was increasing anxiety around global issues such as continued (in some cases deliberate) uncertainty regarding climate change, the re-emergence of radicalized far-right political movements, fear of global and domestic terrorism, the global financial crisis of 2008, and widening social divides along racial, cultural and ideological lines.

Throughout these years, Australian mainstream media and government strove to maintain the country’s image of itself as ‘the lucky country’, despite the ironic tone originally intended for that iconic phrase when it was coined by Donald Horne in 1964. The clash between this image of a carefree nation defined by ‘mateship’ and the country’s increasingly isolationist and anti-humanitarian policies towards refugees, immigration, and First Nations people created an atmosphere of tension and cognitive dissonance that artists were regularly drawn to expose and interrogate.

Rosemary Sorensen highlighted these tensions and ironies in 2009, analysing the speeches given by Australian Prime Minister of the time, Kevin Rudd, for the Australia Day celebrations of the previous and current years. Rudd, she noted, began his 2008 Australia Day speech talking about ‘a great, unrestrained, almost unbridled optimism, almost joy’ in the way the national day is celebrated. ‘We are a nation of youth, a nation of energy, and a nation of ideas and of optimism.’ The following year however, in 2009, the Prime Minister left notions of optimism and hope for his closing remarks, giving his Australia Day speech in Perth: ‘This state is known for its vitality, this state is known for its optimism, this state is known for its determination and it’s can-do attitude. All those values and virtues are going to be needed by the nation in the year which lies ahead.’ᶦ

Sorensen also noted that optimism was a theme in much of the national art community’s programming in the last years of the decade, ‘Queensland Art Gallery director Tony Ellwood recently claimed for artists precisely that role and intention: to cultivate hopeful visions while understanding suffering. Optimism, the gallery’s first in a triennial series focusing on contemporary Australian art, ran as a summer blockbuster show for the 2008-09 holiday season, crowding the work of 50 artists into the generous spaces of the gallery of Modern Art.’ᶦᶦ

Into this climate, Kantor launched Wright’s adaptation of the ultimate Enlightenment era rebuke to the philosophical school of optimism, Voltaire's novella Candide: or Optimism.

In an essay written for the program, Australian philosopher, and writer Damon Young, provided insight into the kind of optimism Voltaire was challenging. Two of the Enlightenment’s leading philosophers, Gottfried Leibniz and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, are regularly credited as the proponents of Optimism as an all encompassing world view. ‘Not garden-variety optimism (I do hope its sunny on Saturday)’, Young explained, ‘but a kind of zealous faith in the perfectibility of things (we can engineer all Saturdays to be sunny). Many scholars believed that the universe could be precisely described and predicted with mathematics; that the mind could be transparently rational; and that principles of reason could explain, order and improve mankind.’ᶦᶦᶦ In her review of the production, Alison Croggon adds that ’All the same, Voltaire wasn’t arguing for pessimism. Rather, he was savagely challenging optimism’s claim that life was ruled by immutable forces and that nothing could be done about it, which was, in Voltaire’s view, a covert form of pessimism.'ᶦᵛ Kate Herbert sums this up succinctly in her review when she notes that it ’reminds us that to believe all will be well if we ‘just stay positive’ is foolish in our world.’ᵛ

In an interview with Sorenson, Wright says of Voltaire’s central character Candide, ‘he’s not suggesting that anyone who is an optimist or anyone who believes everything is getting closer and closer to perfect is a fool, nor does he take the opposite position that we should all be pessimistic and sit around waiting for the end of the world… He occupies some zone in between. He’s a pragmatist and in this world view, the opposite of excessive optimism is realism. That’s what makes his book so 21st century because it comes down to a whole lot of debates about whether you choose to be positive or negative about the future.’ᵛᶦ

Wright’s adaptation of the novella takes its episodic structure, according to him a ‘series of philosophical questions or ideas, strung together with a couple of characters’,ᵛᶦᶦ and gives it a vaudevillian form. Kantor’s production leans into this approach, adding elements of clowning, improvisation, and musical theatre. The inclusion of contemporary pop songs such as Devo’s Beautiful World and D.Ream’s Things Can Only Get Better, is described by reviewer Martin Ball as ’such a feature of the Malthouse style'ᵛᶦᶦᶦ and ’the best so far,‘ and prompts Peter Craven to describe the Malthouse as ‘that site of postmodern song and dance.’ᶦˣ

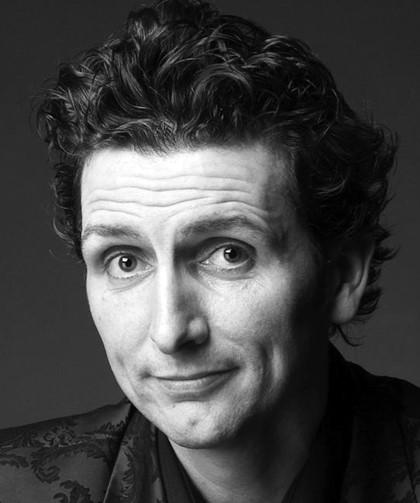

Central to the success of Optimism was the casting of Australian comedian Frank Woodley in the role of Candide. Woodley, one half of the at the time fifteen-year-long comedy partnerships Lano and Woodley with Colin Lane, is regularly described in reviews and interviews for the project as having a wide-eyed optimism, a bewildered decency and the ‘perpetually raised eyebrows and idiot-savant smile’ˣ ideally suited to the role.

Kantor explained approaching Woodley for the role, saying ‘I suppose the impetus behind casting Frank is that optimistic spirit we know in his work. He’s the ultimate optimistic clown and Candide himself is like that. Before he has his realizations, no matter what happens, he’s always trying to get back on the horse. And that’s one way of viewing Candide. It’s a satirical piece but the flow of disasters needs to be offset by the comedy.’ˣᶦ Woodley himself said of his part in the production, ’At that stage there wasn’t a script, but I said yes based on the novel because it was incredible. The level of provocativeness and black comedy puts things like The Chaser and Borat to shame.’ˣᶦᶦ

Candide was emblematic of the kind of risks Kantor’s Malthouse was prepared to take in its programming. As Kantor writes in his directors note for the program, 'The theatre has often been a site of desperate communal escapism, where the worries of the world are set aside while we try to re-find our childish enthusiasm for life. Our production mines many forms of theatrical optimism: pantomime to vaudeville, magic show to Broadway musical, cross-dressing, slapstick stand up to falling over—even drawing room farce. Its silliness hopes to almost unwittingly uncover a darker pattern of entertainment—where the twinkle of the star cloth obscures dreadful evidence of a world in decay.'ˣᶦᶦᶦ

Woodley reflected on the role and his own sense of optimism, saying 'I’m in a period where although I have a blessed life and lots of reasons to be grateful, being optimistic does require more conscious maintenance. In my teens or early 20s I didn’t have to think about it much. Optimism is my natural default setting, but I notice now that if I think about things I can become a bit more depressed.'ˣᶦᵛ

Woodley was joined on stage by a stellar lineup of supporting cast including Barry Otto, Alison Whyte, David Woods and Francis Greenslade. Otto, a veteran of the Australian stage and screen, had a more sanguine take on the themes of the production, saying 'You have to be optimistic today… I’m of the theory that life and happiness is a very simple thing. In the 21st century, a lot of us are distracted with our own lives and we forgot to talk to one another. I think the world has changed a lot, but I’m still optimistic.'ˣᵛ

2009 was also the year of the terrible Black Saturday Bushfires in Victoria, which saw massive destruction to property, 173 fatalities, and more than 400 people injured, in one of the worst bushfires in recorded history. Naturally this tragic event casts a shadow over everything, and the production was no different. It featured prominently in interviews with Whyte, who narrowly survived the fires, escaping with her family from their bush block home to the country pub they owned, where she assisted with relief efforts. In an interview she tells journalist Melissa Kent, 'I don’t know whether it’s because I have an optimistic view on life, but there seems to be a bizarre sense of normality about the whole thing.'ˣᵛᶦ

In his writers note for the program, Wright says 'It seems like the millenarians and catastrophists are always among us. I grew up with nuclear devastation hanging over our heads like a sword of Damocles. I suppose it’s still there. Apparently also nature is in a state of revolt because of our avarice, and every day the jeremiads from climate worriers get more hysterical. The opposing ‘sceptics’ for some reason seem even more depressing. At least for a while there it looked like we’d reached the end of history: and that market capitalism was delivering astonishing wealth for everyone. Maybe it still is. Or will again. Maybe the system isn’t the problem, it’s the faith we put in it.'ˣᵛᶦᶦ

It's a surprisingly ambivalent commentary on a work that seems to inescapably draw our attention to the colossal privilege required to maintain a philosophy of optimism. A telling moment in Candide’s journey involves an encounter with a one legged, one armed slave who opines that his suffering is the 'just the price Europeans pay to have their sugar slightly cheaper.' One can’t help wonder that the European’s aren’t paying this price but instead passing it onto the slave, in the same way Western countries have been doing with colonised nations ever since the beginning of colonisation and continue to do today. Wright himself notes in interview that 'One of the core truths, it seems to me, is that our optimism, our 21st century optimism, the optimism that comes out of Obama, out of Canberra op-ed pieces, the idea that everything will be all right, is born out of an ongoing tacit understanding that the Third World will continue to keep us afloat through their labour and through our exploitation of them.'ˣᵛᶦᶦᶦ

The Malthouse production of Optimism was an important part of Kantor’s extension of the Malthouse brand onto international stages. With the 2009 remount of The Malthouse’s Exit the King premiering on Broadway (and receiving two Tony awards), Optimism was invited to the Edinburgh Festival for 2009 by Festival Director Johnathon Mills. It was part of the festival’s opening week and Frank Woodley was awarded the prestigious Herald Angel award for his performance. Speaking at the opening night of the Malthouse season Mills, a former director of the Melbourne International Arts Festival, told the audience that the 2010 Edinburgh Festival would again feature Victorian artists, stating that 'Part of Edinburgh’s Future should be in Melbourne.'ˣᶦˣ That same night, Victorian Arts Minister Lynne Kosky told the audience 'Scotland and its people feature strongly in Victoria’s history and our sister state relationship has recently been strengthened through Melbourne and Edinburgh’s designations as UNESCO cities of literature.' Earlier that week the minister had announced an arts export grant worth $210,000, saying it was important for Victorian artists to be seen abroad as 'it expands their audience base and generates opportunities for future engagements and collaboration.'ˣˣ

Kantor and Wright’s production of Optimism was an encapsulation of the sometimes edgy, sometimes risky but always thoughtful approach and European focus of the Kantor years. As Martin Ball put it, Optimism 'in many ways represents the clearest expression yet of director Michael Kantor’s collaborative theatre project. A famous text, arresting visual design, and clever use of contemporary music all make for an engaging and entertaining production.'ˣˣᶦ

Optimism was remounted in 2010 at the Sydney Opera House.

Dr . Robert Reid is an independent playwright, theatre historian, immersive performance designer and critic. They were the artistic director of independent theatre company Theatre in Decay and immersive performance and game company, Pop Up Playground. Dr . Rob's plays have been performed by the MTC and Black Swan, and their immersive works have been presented by the MSO, SLV, City of Melbourne, Bell Shakespeare and the Melbourne Football Club. Dr . Rob has a PhD in Australian Theatre History, was a co-founder and co-editor of WitnessPerformance.com and now runs the YouTube channel, Television is Furniture presenting reviews, history, and analysis of contemporary Australian theatre.

Citations & References

ᶦ Sorensen, Rosemary. “Possible Worlds” Arts, Weekend Australia, May 16 – 17 2009

ᶦᶦ Ibid

ᶦᶦᶦ Young, Damon. “Pot Shots at Optimism”, Optimism Theatre Program, May 2009.

ᶦᵛ Croggon, Alison. “Satire flies high in Wright hands,” The Australian, 29 May 2009.

ᵛ Herbert, Kate. “Review”, Theatre, Herald Sun, 29 May 2009.

ᵛᶦ Sorenson, Rosemary. Op. Cit.

ᵛᶦᶦ Ibid

ᵛᶦᶦᶦ Ball, Martin. “A Wide Eyed optimist faithful to Voltaire,” The Age, 29 may 2009.

ᶦˣ Craven, Peter. “The Candide Man Can”, The Age, 16 May 2009.

ˣ Ball, Martin. Op. Cit.

ˣᶦ Craven, Peter. Op. Cit.

ˣᶦᶦ Kernohan, Kathryn. “Ever the Optimist,” The Melbourne Times, 20 May 2009.

ˣᶦᶦᶦ Kantor, Michael. “Directors Notes”, Optimism, Theatre Program, May 2009.

ˣᶦᵛ Kernohan, Op. Cit.

ˣᵛ Bennett, Sally. “Smile is our style,” Herald Sun, 20 May 2009.

ˣᵛᶦ Kent, Melissa. Upfront, M magazine, The Age, May 24 2009.

ˣᵛᶦᶦ Wright, Tom. “Writers Notes”, Optimism, Theatre Program, May 2009.

ˣᵛᶦᶦᶦ Sorenson, Op. Cit.

ˣᶦˣ Usher, Robin. “Southbank to Scotland,” The Age, May 28 2009.

ˣˣ Ibid

ˣˣᶦ Ball, Martin. Op. Cit.

Dr . Robert Reid is an independent playwright, theatre historian, immersive performance designer and critic. They were the artistic director of independent theatre company Theatre in Decay and immersive performance and game company, Pop Up Playground. Dr . Rob's plays have been performed by the MTC and Black Swan, and their immersive works have been presented by the MSO, SLV, City of Melbourne, Bell Shakespeare and the Melbourne Football Club. Dr. Rob has a PhD in Australian Theatre History, was a co-founder and co-editor of WitnessPerformance.com and now runs the YouTube channel, Television is Furniture presenting reviews, history and analysis of contemporary Australian theatre.